This is only the second book in Hindi that I will be reviewing in English. Coincidentally, both of them deal significantly with the Hindustani language. It’s not as if I don’t read the books in Hindi. I do read, but I find it hard to justify their review while writing in English. One of the reasons is, ‘I can’t quote from it directly and in translation, the original flavour is lost.’ The second is that I may not find the appropriate equivalent of the Hindi/Urdu words. Nevertheless, I came to the conclusion that I’ll transliterate the quotations as it is, followed by their meaning in English for the non-Hindi readers.

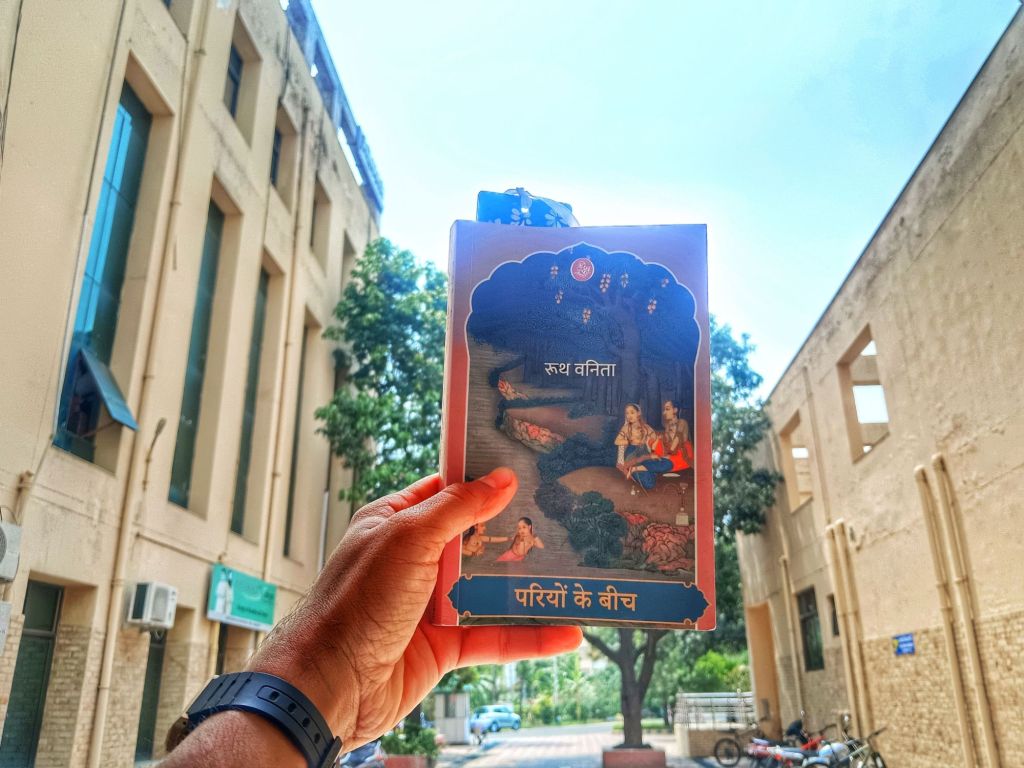

Title: Pariyon ke bich transcreated from Memory of Light

Author and Translator: Ruth Vanita

Genre: Historical/LGBTQ Romance Fiction

Publisher: Rajkamal Prakashan

Narration: First person

Year: 2021

Price: 175/- flipkart

I had the opportunity to grab a signed copy of this book when Prof. Ruth Vanita came to our department to give a talk on ‘Translating Gender and Sexuality in Literature.’ I didn’t know then that Pariyon ke Bich is the translated, to be more precise, transcreated version of her book Memory of Light, published in 2020. Interestingly, the transcreated book, completed by the author herself, came a year later (2021). Had I read the book before, I would have asked more questions, since translation is one of the areas I have a keep interest in.

Pariyon ke bich is a tale of conversations, soliloquies, songs and poems, illustrating the love between Nafi’s Bai and Chapla in pre-independence India. Narrated by Nafi’s, the first-person narrative allows the reader to observe the life of the characters closely. Set in the Nawabi era of Lucknow, a part of the story gives the reader a glimpse of Delhi during the 1700s.

This book can be analysed from multiple perspectives. Among the two evident concerns, the first is the topic on which Prof. Vanita gave the talk, whereas the second, the intricate bond a woman shares with others, their unexpressed desires, with the overtones of same-sex relationships. Alternatively, the novel is also a reflection of the situation of women at the prostitution centre (Kotha). I was startled to know (mentioned by Prof. Vanita) that before the colonial rule, the society was more accepting of same-sex love. It was only after 1857, the situation overturned, making it taboo, and a big question mark was put on such relations. Lihaaf by Chughtai reiterates the same. The reading of the Vedas also illustrates the freedom enjoyed by women. The book presents a secular picture of the Indian society where a Muslim community talks about Kashi, Sanskrit and Natyashastra.

The book is rich in description, delineating every minute detail, including the complexities of the women’s sphere. It won’t be wrong if said that the ‘stream of consciousness’ narrative trope dominates the novel. The readers can peek into the thought process and feelings of the women. It’s also supplemented by ghazals, poems, shayaris, and nazms appropriate to the situation described, which enrich the reading. One of the shayaris (p. 153) that loosely justifies the title of the book is:

“Apni aakhon me us pari ke bagair

Sehar aabad aur ujad hai ek”

However, the extensive description sometimes counteracts the interest of the readers. Since the book is transcreation, a lot of care has been taken to make it a wholesome entity; nonetheless, I would suggest that readers read the English version. It becomes difficult to decipher the Urdu meanings at times.

©Shashank